|

Samurai

Widespread discontent with the dictatorship of the Taira (tie-RAH) clan in Kyoto (key-OH-toe) caused an enormous uprising in 1180.

Five years of brutal civil war ensued, ending when the Minamoto clan overthrew the Taira. The Minamoto handed control of the new

government to a group of loyal warriors, called samurai (SAM-oo-rye). The samurai unified their forces under a code known as the

"way of the warrior" which valued bravery, honor, and strength.

In art, the luxurious tastes and refinement of the Kyoto nobility were replaced by the directness and simplicity of the samurai. The dynamic

spirit of the age demanded art that was similarly big and brash. The civil war had severely damaged many temples, and artists set about

rebuilding, restoring, and replacing lost sculptures. Among the many sculptures produced were pairs of

IDEALIZED

but NATURALISTIC

large Nio guardian figures that stood outside Buddhist temple complexes.

Nio Guardian Figures

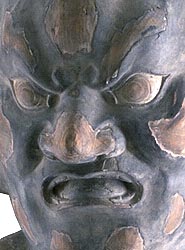

These Nio guardian figures named Misshaku (mish-AH-koo) Kongo (congo) and Naeren (NAY-ren) Kongo (congo) represent the use of overt

power and latent power, respectively. They display the energy and realism characteristic of late 14th-century Japanese sculpture.1

Standing on banks of fluffy clouds, the guardians are enormously muscled half-nude figures. Their features have been skillfully exaggerated

by an artist well versed in the human form. Bulging muscles in their huge chests and arms communicate power even at a great distance.

This exaggerated

REALISM

continues in the Nios' popping veins, extended jaws, and even in their delicate fingernails and toenails. The guardians' hair, pulled

tightly into topknots, adds to their imposing height.

|

|

|

|

Roll over the image to see naturalistic details from the Nio Guardian Figures |

|

Detail showing decorative features from the Nio Guardian Figures |

For all of their power, the Nio are also decorative. Their flower-shaped nipples and rippled rib cages form an elegant

PATTERN.

The dark and light areas on the sculptures are traces of

GESSO

and black LACQUER

that once covered their surfaces. Flesh-colored pigments covered portions of the lacquer.

The Nio exhibit tremendous energy. Their arms, legs, and clublike feet dramatically jut into space, and drapery swirls violently around them.

The Nio's bulging eyes, furrowed brows, flaring nostrils, and distorted grimaces bring their faces to life.

Conceived as a pair, the Nio complement each other. Misshaku Kongo, representing power in action, bares his teeth and raises his fist in

action, while Naeren Kongo, representing potential might, holds his mouth tightly closed and waits with both arms tensed but lowered.

Each Nio figure represents a particular cosmic sound. Misshaku Kongo's open mouth sounds out "ah," meaning birth. Naeren Kongo

sounds "om," meaning death. Thus, in two cosmic sounds life is encapsulated at a temple doorway, reminding viewers that life

is fleeting and that good karma is necessary to avoid rebirth on the Wheel of Life.2

|

|

|

|

Detail of Misshaku Kongo making the cosmic sound "ah" from the Nio Guardian Figures |

|

Detail of Naeren Kongo's making the cosmic sound "om" from the Nio Guardian Figures |

1 The Nio guardians were created by a joined woodblock carving technique called yosegi. Each is

created from many pieces of wood pegged together. This allowed the artists to create monumental figures with dynamic poses. The seams

and cracks were covered with fabric or paper. The surface was then covered with layers of gesso, (baked seashells and water) and black

lacquer. Details such as the pupils of the eyes and the decorative pattern on the drapery were also painted.

2 Buddhists believe that everyone is subject to what they call the Wheel of Life, that is, that

all souls are doomed to be reincarnated endlessly unless they gather enough good karma (good deeds, good spirituality) to become

enlightened, and able to enter nirvana (extinction of the self). Even if one cannot earn enough good karma to become enlightened,

good or bad karma decides what one's next life will be like.

|