|

My photographs

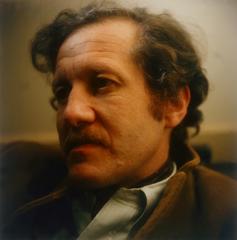

tried to find the politicians at their most wary, most vulnerable,

and perhaps most truthful moments. I wanted the photographs to reveal

the person through stance and stare, when he or she was most reflective

or off guard, in order to measure the person and event unfolding.

–Jerome

Liebling, The Minnesota Photographs, 1997

|

Besides teaching photography at

the University of Minnesota, Jerome Liebling was often hired by politicians

to make photos of their campaigns. Liebling was always on the lookout

for pictures that revealed a politician’s true character, even though

that wasn’t exactly his assignment.

This photograph, taken at a rally in Minneapolis, is a good example of

what the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive

moment.” The decisive moment is a concept that photographers everywhere

understand. Cartier-Bresson explains, “Sometimes you have the feeling

that here are all the makings of a picture–except for just one thing

that seems to be missing. You wait and wait, and then finally you press

the button–and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t

know why) that you’ve really got something. Later, to substantiate

this, you can take a print of this picture . . . and you’ll discover

that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively

fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been

both formless and lifeless.” (The Decisive Moment, 1952)

Liebling certainly caught the two politicians in the photo at a decisive

moment. Their faces at this moment tell a story about their temperaments–one

worried, uncomfortable and tense; the other relaxed, in control, with

a tiny triumphant smile on his face. It is this sort of attitude that

politicians don’t like to reveal, but it was just what Liebling was

looking for.

|